The Silent Progression: Understanding How Insulin Resistance Develops Years Before Diabetes

Diabetes doesn't happen overnight. For most people who develop type 2 diabetes, the metabolic machinery has been quietly malfunctioning for 5-10 years—sometimes even decades—before blood glucose levels rise enough to trigger a diagnosis. This prolonged development phase centers around a critical metabolic condition called insulin resistance. Understanding this process is not just academic; it could be the key to preventing millions of diabetes cases worldwide.

The Insulin Resistance Spectrum

Insulin resistance exists on a spectrum rather than as a binary condition. Think of it as a gradual decline in your body's responsiveness to insulin, similar to how hearing loss often develops so gradually that you don't notice it until it significantly impacts your life.

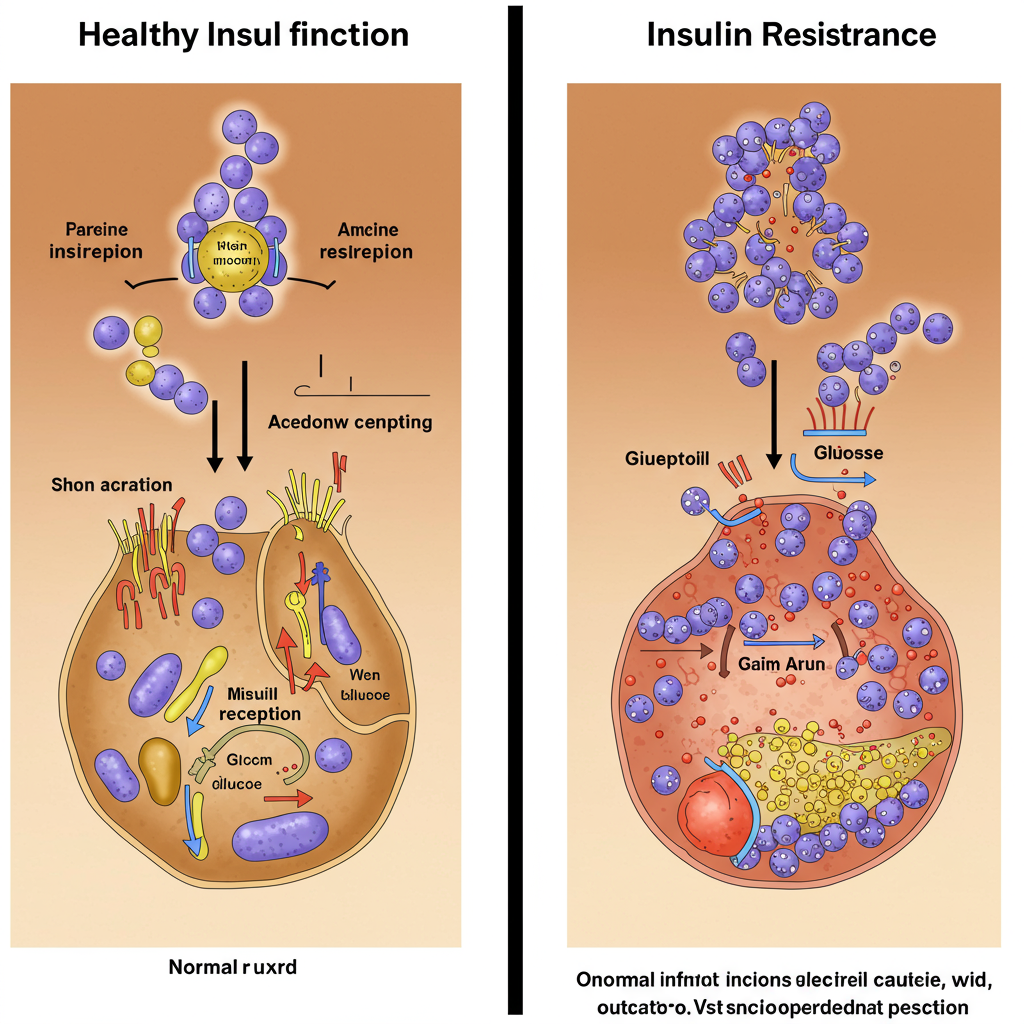

In a healthy metabolic state, your pancreas secretes insulin when you consume carbohydrates. This insulin acts as a key, unlocking cells to allow glucose to enter and be used for energy. When insulin resistance begins, your cells start becoming less responsive to this hormonal signal. The pancreas compensates by producing more insulin—a condition called hyperinsulinemia—to maintain normal blood glucose levels.

This compensatory mechanism can be remarkably effective, sometimes for years or even decades. Your fasting glucose and even post-meal glucose levels might remain normal during this time, creating a false sense of metabolic security. Meanwhile, your insulin levels are silently rising, working overtime to overcome the resistance at the cellular level.

The Multiple Pathways to Resistance

What triggers this metabolic dysfunction in the first place? Insulin resistance rarely has a single cause; it typically develops through multiple, interconnected pathways:

-

Energy Surplus: Consistently consuming more calories than your body needs, particularly from refined carbohydrates and ultra-processed foods, creates a state of energy excess. This abundance of energy overwhelms normal metabolic processes.

-

Ectopic Fat Accumulation: When energy intake chronically exceeds expenditure, fat begins accumulating in places it shouldn't—like the liver, muscles, and pancreas. This "ectopic fat" disrupts normal cellular function and significantly impairs insulin signaling.

-

Inflammation: Both poor diet and excess body fat (especially visceral fat around the organs) trigger low-grade, chronic inflammation. This inflammatory state directly interferes with insulin receptor function and downstream signaling pathways.

-

Sedentary Lifestyle: Regular physical activity naturally enhances insulin sensitivity. Without it, muscles become less efficient at glucose uptake, contributing to whole-body insulin resistance.

The concerning reality is that these processes can operate silently for years. Your annual physical might show normal fasting glucose levels even while significant metabolic dysfunction develops beneath the surface.

The Warning Signs We Often Miss

While blood glucose remains normal during early insulin resistance, there are several clinical indicators that can serve as early warning signs:

Elevated Fasting Insulin: Perhaps the most direct measure of developing insulin resistance is an elevated fasting insulin level. Unfortunately, this test isn't routinely performed in standard medical checkups.

Triglyceride to HDL Ratio: A ratio above 3.0 (or above 2.0 for some populations) often correlates with insulin resistance, even when glucose metrics appear normal.

Waist Circumference: Abdominal fat, particularly visceral fat that surrounds internal organs, strongly correlates with insulin resistance. A waist circumference greater than 40 inches in men or 35 inches in women (with lower thresholds for some ethnic groups) suggests metabolic dysfunction may be present.

Acanthosis Nigricans: This skin condition, characterized by darkened, velvety patches in body folds and creases, directly reflects hyperinsulinemia and is often visible years before diabetes develops.

Postprandial Fatigue: Feeling unusually tired after carbohydrate-rich meals can indicate that your body is struggling with exaggerated insulin responses to manage glucose.

Breaking the Progression

The extended timeline of insulin resistance development is actually good news. It provides a substantial window for intervention—often years or decades—before diabetes manifests. Research increasingly shows that addressing insulin resistance early can prevent or significantly delay the onset of diabetes.

Effective strategies include:

- Reducing processed carbohydrate intake while emphasizing protein, healthy fats, and fiber

- Implementing time-restricted eating to reduce insulin secretion duration

- Prioritizing regular exercise, particularly strength training and high-intensity intervals

- Improving sleep quality and addressing sleep disorders like sleep apnea

- Using continuous glucose monitors to identify personal glucose triggers

The key is recognizing that normal glucose readings don't necessarily indicate metabolic health. By focusing on insulin resistance rather than waiting for elevated glucose, we can intervene decades earlier in the disease process.

Understanding this prolonged development period transforms how we should think about diabetes prevention. It's not about catching the disease early—it's about recognizing and reversing the underlying metabolic dysfunction years before the disease even begins.

References:

Tabák AG, Jokela M, Akbaraly TN, et al. Trajectories of glycaemia, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion before diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2215-2221.

Taylor R. Calorie restriction for long-term remission of type 2 diabetes. Clinical Medicine. 2019;19(1):37-42.