In the world of metabolic health and diabetes management, few topics generate as much debate as fasting. While intermittent fasting has gained mainstream popularity, extended fasting—lasting 24 hours or more—remains somewhat controversial. As someone deeply immersed in the science of metabolic health, I want to share an evidence-based perspective on whether these longer fasts truly deliver on their promises, particularly for those concerned with diabetes prevention and management.

The Metabolic Magic of Extended Fasting: What Science Tells Us

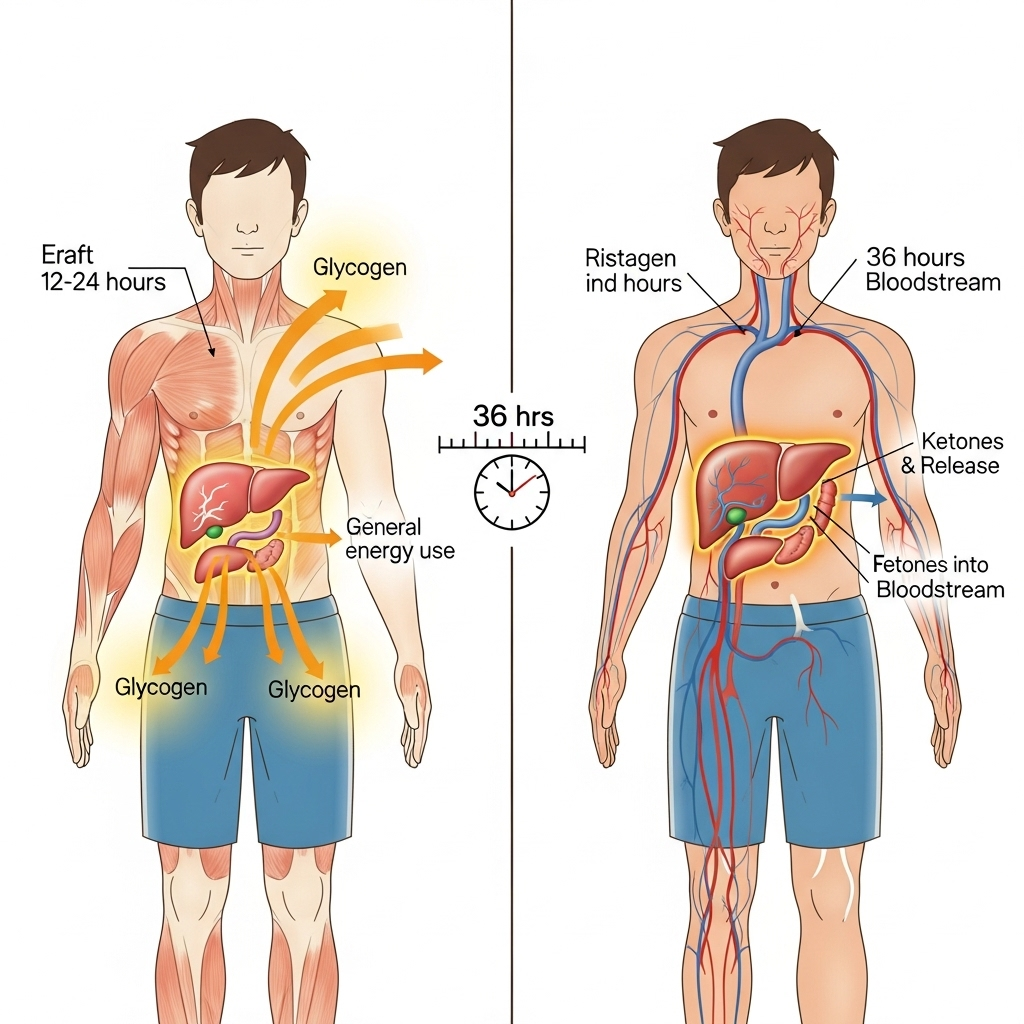

When we extend a fast beyond the typical overnight period to 24 hours or more, several fascinating physiological changes occur. The body, deprived of incoming glucose, must shift fuel sources. After depleting glycogen stores (usually within 24-36 hours), we enter a state of nutritional ketosis, where the liver converts fatty acids into ketone bodies that serve as an alternative fuel source for the brain and body.

This metabolic switch can trigger beneficial cascading effects:

-

Enhanced insulin sensitivity: Extended periods without food give insulin receptors a chance to "reset," potentially improving their responsiveness when you resume eating.

-

Autophagy activation: This cellular cleanup process helps remove damaged components and may be particularly beneficial for metabolic health. However, it's important to note that while autophagy is well-documented in animal studies, the evidence in humans remains limited.

-

Reduced inflammation: Some studies suggest that longer fasts can lower inflammatory markers, which is particularly relevant for diabetes since chronic inflammation plays a role in insulin resistance.

-

Decreased liver fat: In individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)—a condition closely linked with insulin resistance—extended fasting has shown promise in reducing hepatic fat accumulation.

However, there's a critical caveat: while these benefits appear impressive in short-term studies, many don't persist beyond a few months, even when weight loss is maintained. This raises important questions about the long-term efficacy of extended fasting as a diabetes management strategy.

The Muscle Dilemma: The Hidden Cost of Extended Fasts

Perhaps the most concerning aspect of longer fasts is their impact on body composition. Research indicates that a substantial portion—sometimes up to two-thirds—of the weight lost during extended fasts may come from lean mass rather than fat tissue.

This is problematic because muscle mass plays a crucial role in glucose disposal and metabolic health. Skeletal muscle is our largest glucose sink, responsible for clearing approximately 70-80% of blood glucose after a meal. Losing this metabolically active tissue can potentially worsen long-term insulin sensitivity, creating a counterproductive scenario for diabetes management.

For those who are significantly overweight or have substantial insulin resistance, the benefits of fat loss during extended fasting might temporarily outweigh the drawbacks of muscle loss. However, for leaner individuals or those who have already improved their metabolic health, the risk-benefit calculation shifts unfavorably.

The research indicates a concerning pattern: while extended fasts can produce rapid improvements in various markers, including glucose control, these benefits often disappear within 3-4 months, even when weight loss is maintained. This suggests that the metabolic benefits may be tied more to the active process of losing weight rather than the fasting mechanism itself.

Finding a Sustainable Middle Ground

Given these complexities, what approach makes the most sense for those concerned with diabetes prevention or management?

For most people, shorter fasting strategies likely offer a more sustainable and beneficial approach:

-

Time-restricted eating (TRE): Limiting daily eating to a window of 8-10 hours can provide many of the benefits of fasting without the same risks to muscle mass. For example, finishing dinner by 7 PM and not eating again until 7-9 AM the next morning gives your body a 12-14 hour fasting period daily.

-

Intermittent fasting: Approaches like the 5:2 method (eating normally five days per week and restricting calories to about 500-600 on two non-consecutive days) can provide metabolic benefits while allowing for adequate protein intake to preserve muscle.

-

Protein-modified fasting: If attempting longer fasts, maintaining some protein intake (perhaps 15-30g per day) may help mitigate muscle loss while still providing many of the benefits of fasting.

These modified approaches tend to be more sustainable long-term and may strike a better balance between metabolic benefits and maintaining muscle mass.

Practical Considerations: Is Extended Fasting Right for You?

If you're considering trying an extended fast despite the caveats, here are some important considerations:

Who might benefit:

- Individuals with significant insulin resistance or prediabetes looking for a metabolic "reset"

- Those with substantial excess body fat where the benefits of fat loss may temporarily outweigh muscle concerns

- People with fatty liver disease (under medical supervision)

Who should avoid extended fasting:

- Anyone with Type 1 diabetes

- Those with a history of eating disorders

- Pregnant or breastfeeding women

- Older adults who are already at risk for sarcopenia (age-related muscle loss)

- Very lean individuals or those focused on muscle preservation

- People on certain medications that require food intake

If you do decide to try an extended fast, consider these practical tips:

-

Medical supervision: Work with a healthcare provider who understands fasting physiology.

-

Electrolyte management: During longer fasts, maintain proper sodium, potassium, and magnesium intake.

-

Breaking the fast thoughtfully: After an extended fast, break it gently with a moderate-sized, protein-focused meal to minimize blood sugar spikes.

-

Monitoring: If possible, use tools like continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) to track your metabolic response.

-

Post-fast nutrition: Focus on adequate protein intake (at least 1.2-1.6g/kg body weight) and resistance training to rebuild any lost muscle tissue.

The most sustainable approach for most people concerned with diabetes prevention or management isn't necessarily found in extended fasting, but rather in consistent habits: prioritizing protein, minimizing ultra-processed foods, incorporating daily movement, managing stress, and optimizing sleep. For many, adding a gentle time-restricted eating window of 10-12 hours may provide additional benefits without the risks of longer fasts.

Remember that metabolic health is a marathon, not a sprint. The interventions that work best are those you can maintain consistently for years, not those that provide dramatic short-term results followed by rebound effects.

References

Mattson, M. P., Longo, V. D., & Harvie, M. (2017). Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Research Reviews, 39, 46-58.

Gabel, K., Hoddy, K. K., Haggerty, N., Song, J., Kroeger, C. M., Trepanowski, J. F., Panda, S., & Varady, K. A. (2018). Effects of 8-hour time restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: A pilot study. Nutrition and Healthy Aging, 4(4), 345-353.