Rewiring Your Relationship with Food: The Neuroscience of Eating Habit Change

In managing diabetes, we often focus on what to eat, but rarely discuss how to actually change our eating habits long-term. As someone living with diabetes, I've found that understanding the brain mechanisms behind habit formation has been transformative in my own health journey. Today, let's explore the fascinating neuroscience of behavior change and how we can apply it to establish healthier eating patterns that stick.

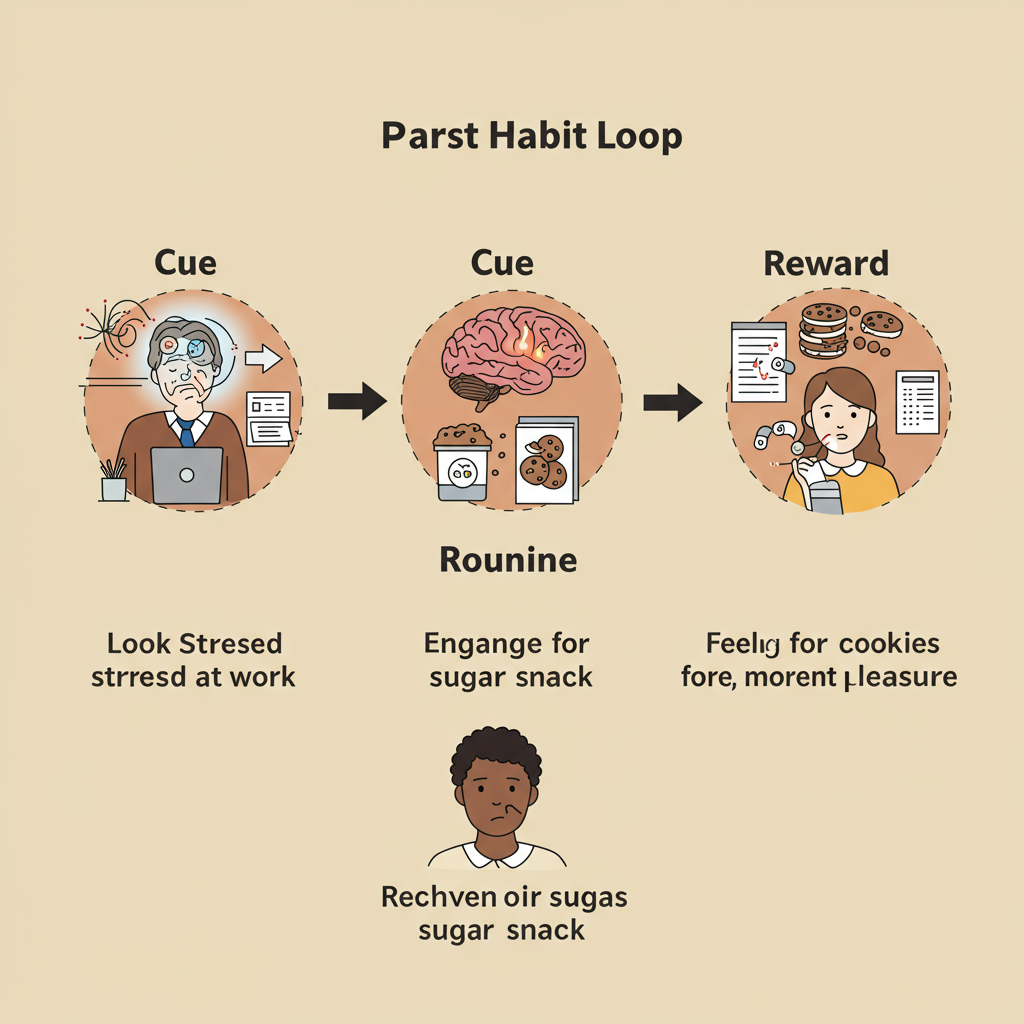

The Habit Loop: Understanding Why Change Is Hard

Our brains are efficiency machines, designed to automate behaviors that we repeat regularly. This is the foundation of habits. Neuroscientists have identified a three-part "habit loop" consisting of a cue, a routine, and a reward. For people with diabetes, problematic eating habits often follow this pattern:

- Cue: Stress, boredom, social situations, or even specific times of day

- Routine: Reaching for high-carb comfort foods or sugary snacks

- Reward: The immediate dopamine release and pleasure from these foods

What makes change particularly challenging is that these patterns become deeply encoded in our basal ganglia, a brain region responsible for habit formation. The neural pathways get stronger with repetition, making the behavior increasingly automatic and difficult to override with conscious decision-making.

This explains why willpower alone is rarely effective for long-term habit change. We're literally fighting against established neural architecture.

Leveraging Neuroplasticity: The Brain's Capacity for Change

The good news is that our brains possess remarkable neuroplasticity—the ability to form new neural connections throughout life. This means that with the right approach, we can "rewire" our eating habits.

Research shows that habit change is most effective when we:

1. Focus on cue awareness: The first step is becoming conscious of what triggers problematic eating. By simply noting "I'm reaching for this cookie because I'm stressed" without judgment, we activate the prefrontal cortex, bringing automatic behaviors into conscious awareness.

2. Implement habit substitution rather than elimination: Complete elimination creates a reward void, making relapse likely. Instead, replace the problematic behavior with a healthier one that provides a similar reward. For example, if stress eating is your challenge, substitute a short walk or breathing exercise that can also reduce stress.

3. Create environmental changes: Our environment powerfully shapes behavior, often without our awareness. Restructuring your physical space—keeping healthy snacks visible and less optimal choices out of sight—can reduce the cognitive load required for better choices.

4. Use "implementation intentions": These are specific if-then plans that connect situational cues with desired responses. For example: "If I feel stressed at work, then I will drink a glass of water and eat my prepared veggie snack." Research shows these concrete plans are far more effective than vague intentions.

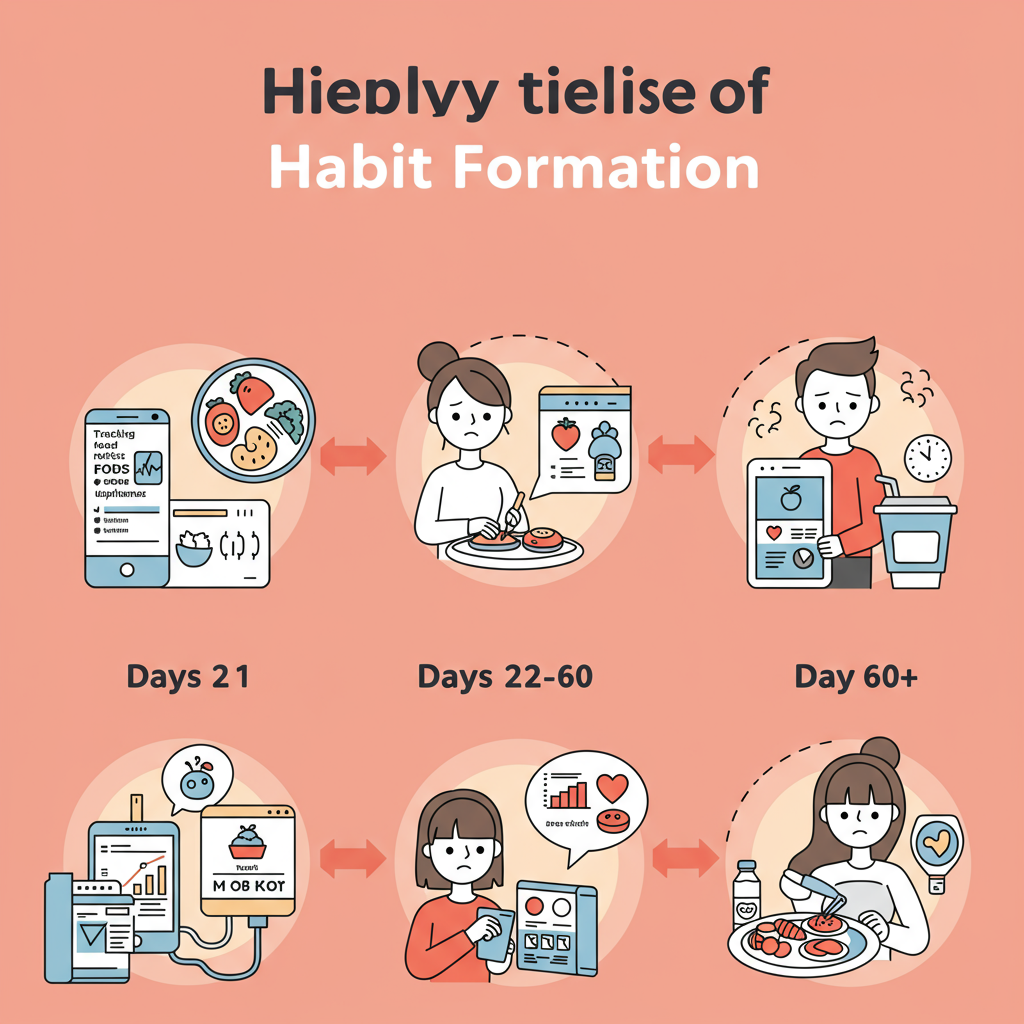

The Timeline of Habit Change for Diabetes Management

Contrary to popular belief, research suggests that the "21 days to form a habit" idea is oversimplified. Studies show that habit formation typically takes anywhere from 18 to 254 days, with an average of 66 days—and this varies based on behavior complexity and individual differences.

For people with diabetes, we need to recognize this realistic timeline and prepare accordingly:

-

First few weeks (Days 1-21): This period requires the most conscious effort and may feel uncomfortable as your brain is actively working against established neural pathways. Glucose monitoring during this phase provides valuable feedback to reinforce new behaviors.

-

Middle phase (Days 22-60): Gradually, new neural pathways strengthen, and the new behaviors require less conscious effort. However, under stress or fatigue, the brain may default to old patterns. This is normal and not a sign of failure.

-

Automaticity phase (Day 60+): Eventually, the new habits become encoded in the basal ganglia, requiring minimal conscious effort. The key is consistency through the earlier phases to reach this point.

Understanding this neurological timeline helps set realistic expectations and prevents the discouragement that often derails habit change efforts.

Conclusion: Small Changes, Big Results

The science of neuroplasticity gives us hope: meaningful change is possible regardless of how long we've had certain eating habits. The key is working with our brain's mechanisms rather than against them.

For those managing diabetes, focus on implementing one small, sustainable change at a time rather than overhauling your entire diet overnight. Track not just your glucose levels but also your habit triggers and responses. Over time, these incremental shifts in behavior can create profound improvements in glucose control and overall health.

Remember that occasional setbacks aren't failures—they're valuable data points in your behavior change journey and normal parts of the neurological rewiring process.

References:

Gardner, B., Lally, P., & Wardle, J. (2012). Making health habitual: the psychology of 'habit-formation' and general practice. British Journal of General Practice, 62(605), 664-666.

Wood, W., & Rünger, D. (2016). Psychology of habit. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 289-314.