As someone deeply immersed in the metabolic health space, I often observe that discussions around food sensitivities focus heavily on allergies and intolerances to proteins and specific food compounds. However, for those with diabetes or metabolic dysfunction, there's another critical form of "food sensitivity" that deserves our attention: carbohydrate sensitivity.

In today's post, I want to explore how the distinction between food allergies and intolerances provides a useful framework for understanding the unique carbohydrate processing challenges faced by people with diabetes. This perspective can transform how we approach dietary management in metabolic disease.

The Spectrum of Food Sensitivities: Where Does Diabetes Fit?

Let's start by clarifying the traditional distinction between food allergies and intolerances:

Food allergies involve the immune system reacting to specific food proteins, often through IgE antibodies, triggering inflammatory cascades that can range from mild symptoms to life-threatening anaphylaxis. The "Big Nine" allergens (fish, shellfish, milk, eggs, soy, wheat, tree nuts, peanuts, and now sesame) are responsible for most allergic reactions.

Food intolerances, in contrast, don't typically engage the immune system in the same way. Instead, they involve enzyme deficiencies (like lactase for lactose intolerance) or chemical sensitivities that prevent proper food processing, leading to symptoms that are uncomfortable but rarely life-threatening.

But where does diabetes fit in this paradigm? I propose we consider carbohydrate sensitivity in diabetes as a metabolic intolerance – one with profound implications for long-term health.

Carbohydrate Sensitivity: The Overlooked Metabolic Intolerance

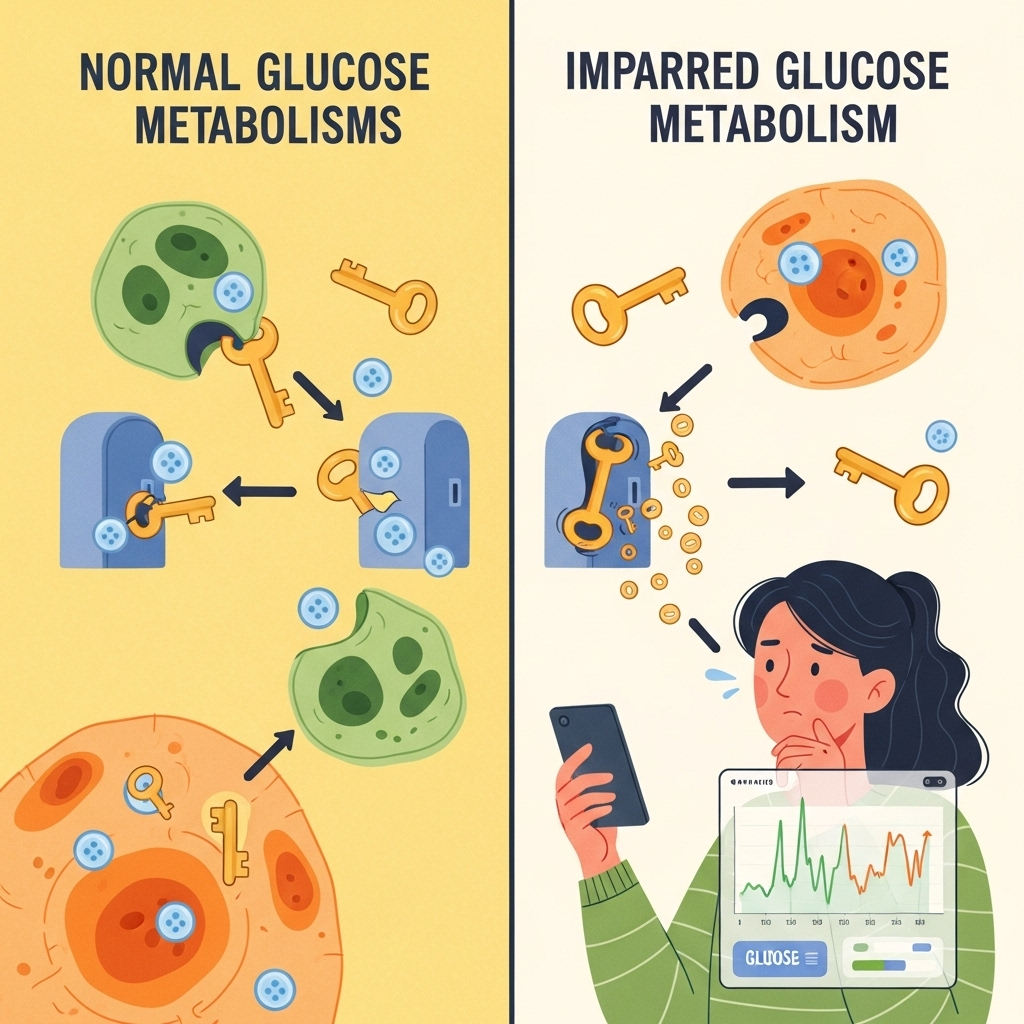

In healthy individuals, the body efficiently processes carbohydrates through a sophisticated hormonal response. Insulin is released in precise amounts, at the right time, to help shuttle glucose from the bloodstream into cells where it's used for energy or stored for later use.

For people with diabetes, this system is fundamentally disrupted:

- Type 1 diabetes: The immune system attacks insulin-producing beta cells, creating an absolute insulin deficiency

- Type 2 diabetes: Progressive insulin resistance develops, where cells become increasingly unresponsive to insulin's signals, often followed by relative insulin insufficiency

This dysfunction creates what we might call "carbohydrate intolerance" or "glucose intolerance" – terms actually used in clinical settings but rarely explained in the context of food sensitivity.

The mechanism is straightforward yet profound:

- Carbohydrates are consumed and broken down into glucose

- Without proper insulin action, glucose accumulates in the bloodstream

- This hyperglycemia triggers both acute symptoms and long-term tissue damage

- Unlike traditional food intolerances that primarily cause discomfort, untreated carbohydrate intolerance leads to serious complications affecting the cardiovascular system, kidneys, eyes, and nerves

Management Parallels: Lessons from Traditional Food Sensitivities

What's fascinating is how management strategies for traditional food intolerances parallel optimal approaches for diabetes:

Identification and monitoring:

- For lactose intolerance, people learn which dairy products and what quantities trigger symptoms

- For diabetes, continuous glucose monitors now allow real-time feedback on how specific carbohydrates affect blood glucose

Personalized thresholds:

- Someone with mild histamine intolerance might tolerate small amounts of trigger foods

- Similarly, carbohydrate tolerance in diabetes exists on a spectrum – some individuals might handle moderate amounts of certain carbohydrates, while others experience glucose spikes from even minimal exposure

Supplementation strategies:

- Lactase enzyme supplements help those with lactose intolerance

- Exogenous insulin (or medications enhancing endogenous insulin action) serves as the "missing enzyme" for carbohydrate metabolism in diabetes

Modified exposure:

- Those with FODMAPs sensitivities may reduce portion sizes or choose low-FODMAP alternatives

- People with diabetes can select carbohydrates with lower glycemic impact, adjust timing and context of carbohydrate consumption, or implement strategic exercise to improve glucose disposal

The key difference? While traditional food intolerances primarily cause temporary discomfort, carbohydrate intolerance in diabetes silently damages tissues throughout the body when left unaddressed. This makes understanding and managing this metabolic intolerance all the more critical.

Beyond Avoidance: Metabolic Flexibility as the Goal

While the allergy-intolerance framework is useful for understanding diabetes, we need to move beyond simple avoidance strategies. The goal in diabetes management isn't necessarily complete carbohydrate elimination but rather developing metabolic flexibility – the ability to efficiently use different fuel sources (including carbohydrates) with minimal blood glucose excursions.

Strategies to enhance metabolic flexibility include:

-

Strategic carbohydrate selection: Focusing on nutrient-dense, fiber-rich sources that produce minimal glucose spikes

-

Meal sequencing: Consuming protein, fat, and fiber before carbohydrates to blunt glucose responses

-

Strength training: Building muscle mass to improve glucose disposal pathways

-

Zone 2 exercise: Enhancing mitochondrial capacity and insulin sensitivity

-

Adequate sleep and stress management: Addressing factors that independently worsen insulin resistance

-

Time-restricted eating: Leveraging the body's circadian rhythms to optimize metabolic function

-

Medication and supplementation: Thoughtfully using tools from metformin to berberine when appropriate

The beauty of this approach is that it acknowledges the reality of carbohydrate sensitivity while providing a pathway toward improved metabolic health rather than simply imposing lifelong restrictions.

Conclusion: Reframing Diabetes as a Food Sensitivity

Understanding diabetes through the lens of food sensitivity – specifically carbohydrate intolerance – offers both practical insights and psychological benefits. It removes blame while emphasizing the biological nature of the condition. It also highlights how the management principles used for other food sensitivities can be powerfully applied to diabetes care.

By recognizing carbohydrate sensitivity as a legitimate metabolic intolerance, we can approach diabetes management with greater precision, compassion, and effectiveness. The goal isn't just avoiding glucose spikes but rebuilding metabolic health one meal, one workout, and one good night's sleep at a time.

Whether you have diabetes yourself or support someone who does, I hope this framework helps you navigate the complex relationship between food and metabolism with greater confidence and clarity.

References:

-

Ludwig DS, Ebbeling CB. The Carbohydrate-Insulin Model of Obesity: Beyond "Calories In, Calories Out". JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(8):1098-1103. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2933

-

Hallberg SJ, McKenzie AL, Williams PT, et al. Effectiveness and Safety of a Novel Care Model for the Management of Type 2 Diabetes at 1 Year: An Open-Label, Non-Randomized, Controlled Study. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9(2):583-612. doi:10.1007/s13300-018-0373-9