Beyond the Grain: How Refined Carbs and Whole Grains Differently Impact Your Blood Sugar

When it comes to managing diabetes or maintaining stable blood glucose levels, not all carbohydrates are created equal. The difference between refined carbohydrates and whole grains can significantly impact your glycemic response and, ultimately, your health. Let's dive into why this distinction matters and how making informed choices can help you better manage your blood sugar.

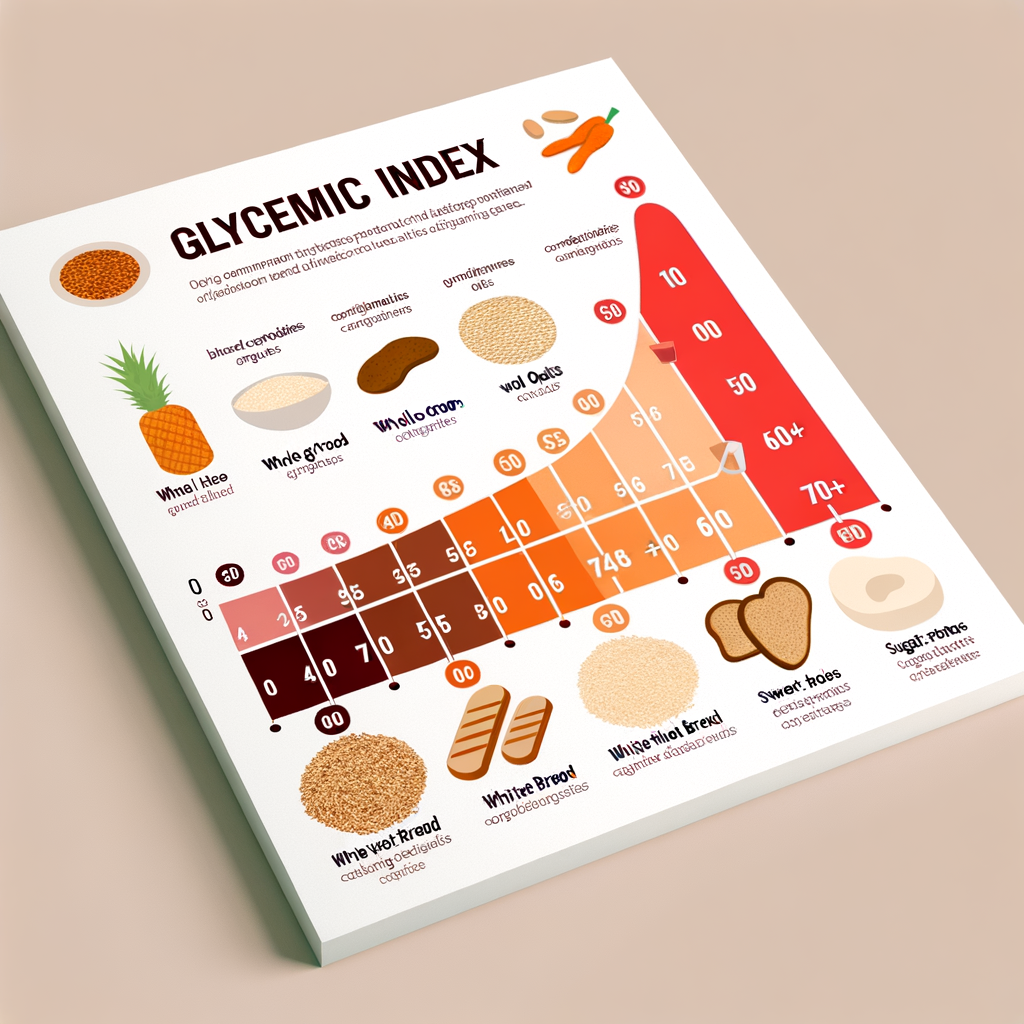

Understanding the Glycemic Index: A Quick Primer

Before we compare refined carbs and whole grains, it's helpful to understand the glycemic index (GI). This numerical system rates foods based on how quickly they raise blood glucose levels. Foods with a high GI (70 or above) cause rapid spikes, while low-GI foods (55 or below) lead to more gradual increases.

The glycemic load (GL) takes this concept further by accounting for portion sizes—because sometimes we eat very little of high-GI foods or larger amounts of lower-GI foods.

Refined Carbohydrates: The Blood Sugar Rollercoaster

What Makes a Carb "Refined"?

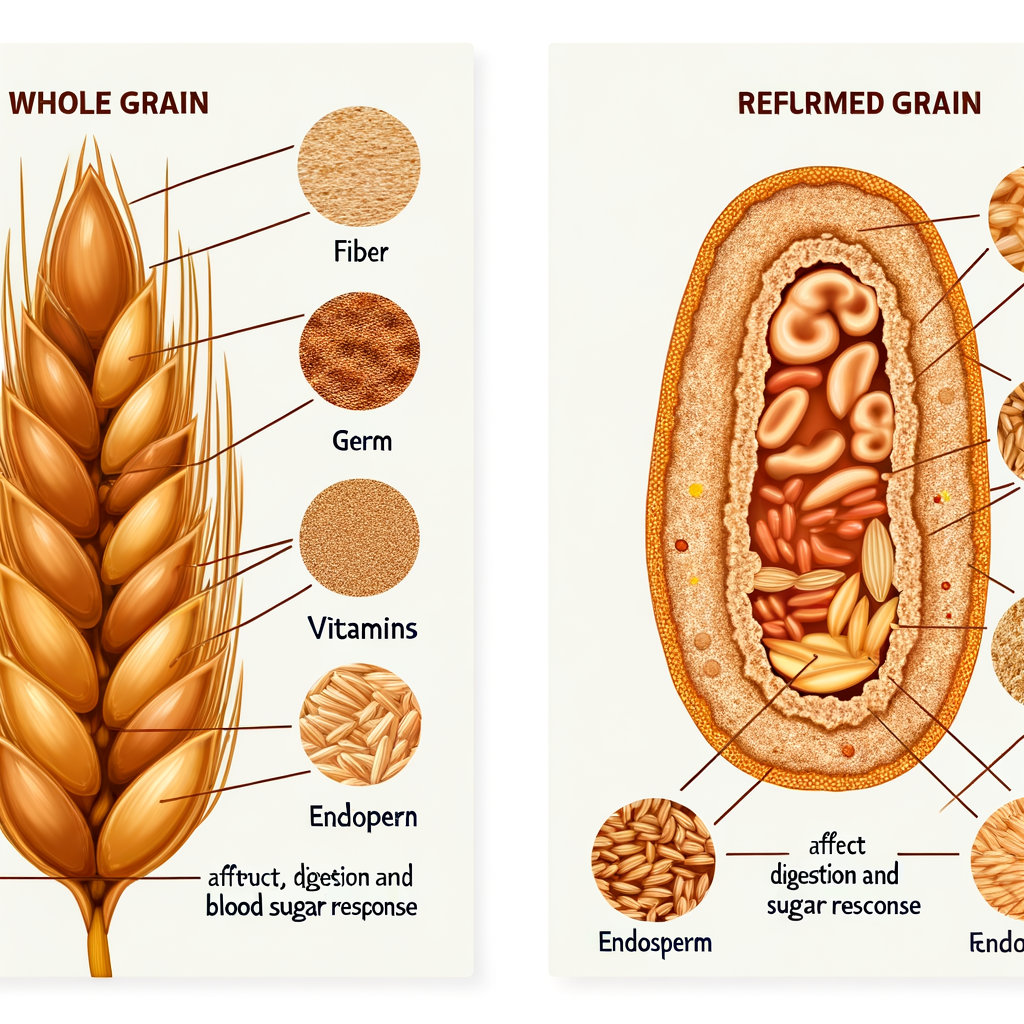

Refined carbohydrates have undergone processing that removes the bran and germ—essentially stripping away fiber, minerals, and vitamins. Common examples include:

- White bread

- White rice

- Regular pasta

- Most breakfast cereals

- Pastries and cookies

- White flour products

The Glycemic Impact

When you consume refined carbs, your body can break them down quickly due to their simple structure. This leads to:

- Rapid glucose absorption: Blood sugar levels rise sharply, often within minutes

- Insulin surge: Your pancreas must release large amounts of insulin to manage the glucose flood

- The crash: After the spike comes the fall—often leaving you hungry and craving more carbs

For people with diabetes, these dramatic fluctuations are particularly problematic, making blood sugar harder to control and potentially contributing to insulin resistance over time.

Whole Grains: Steady Energy Release

What Qualifies as "Whole"?

Whole grains contain all parts of the grain kernel—the bran, germ, and endosperm. Examples include:

- Brown rice

- Quinoa

- Oats

- Barley

- Whole wheat bread (true whole wheat, not just "wheat bread")

- Bulgur

- Farro

The Glycemic Advantage

The intact structure of whole grains offers several benefits:

- Fiber barrier: The natural fiber slows digestion and glucose absorption

- Gradual release: Blood sugar rises more slowly and steadily

- Extended satiety: You feel fuller longer, reducing the likelihood of overeating

- Lower insulin demand: Your pancreas can release insulin more gradually

For someone managing diabetes, these characteristics translate to better glycemic control and fewer challenging blood sugar swings.

The Science Behind the Difference

The stark contrast between refined and whole grains goes beyond their GI values. Research has shown that the fiber in whole grains acts as a physical barrier, literally slowing down digestive enzymes' access to the starch molecules.

Additionally, whole grains contain beneficial compounds that may improve insulin sensitivity over time. These include:

- Magnesium, which plays a role in glucose metabolism

- Phenolic compounds with antioxidant properties

- Plant sterols that may help with inflammation

A study published in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition found that replacing refined grain products with whole grains improved fasting insulin levels and insulin sensitivity in overweight adults—even without weight loss.

Real-World Application: Making the Switch

Transitioning from refined to whole grains doesn't have to happen overnight. Here are practical steps to gradually transform your plate:

Start with Breakfast

- Replace sugary cereals with steel-cut or rolled oats

- Swap white toast for true whole grain bread (look for "whole wheat flour" as the first ingredient)

- Try overnight oats with berries instead of instant flavored oatmeal packets

Lunch and Dinner Makeovers

- Use brown rice instead of white

- Experiment with ancient grains like quinoa or farro in salads

- Choose whole wheat pasta or legume-based alternatives

- Try substituting half your white rice with riced cauliflower as a transition strategy

Reading Labels Effectively

Don't be fooled by marketing terms like "made with whole grains" or "multigrain." Instead:

- Look for "100% whole grain" or "100% whole wheat"

- Check the ingredients list—whole grains should be first

- Examine the fiber content—higher is generally better

- Be wary of added sugars, which can negate some benefits

Beyond GI: The Bigger Health Picture

While glycemic impact is important, especially for diabetes management, the benefits of whole grains extend further. Regular consumption has been associated with:

- Reduced risk of heart disease

- Better weight management

- Improved digestive health

- Lower inflammation markers

Even for those without diabetes, maintaining stable blood glucose can help prevent energy crashes, reduce cravings, and potentially lower the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the future.

The Bottom Line

The difference between refined carbohydrates and whole grains isn't just nutritional trivia—it's a meaningful distinction that affects your short-term blood glucose response and long-term health. By understanding this impact and gradually shifting your choices toward whole grains, you can enjoy more stable energy levels and better glycemic control.

Remember that individual responses to foods vary, so using a continuous glucose monitor or regular blood sugar testing can help you understand your unique response to different grain products. What works best for your body might require some personal experimentation, but the science clearly points toward whole grains as the better option for most people, especially those concerned with blood sugar management.

References:

Aune, D., Norat, T., Romundstad, P., & Vatten, L. J. (2013). Whole grain and refined grain consumption and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. European Journal of Epidemiology, 28(11), 845-858.

Jenkins, D. J., Kendall, C. W., Augustin, L. S., Franceschi, S., Hamidi, M., Marchie, A., Jenkins, A. L., & Axelsen, M. (2002). Glycemic index: overview of implications in health and disease. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 76(1), 266S-273S.