The Hidden Link: How Stress Hormones Drive Your Blood Sugar Rollercoaster

In the intricate dance of metabolism, hormones serve as the choreographers, directing how our bodies process energy. While insulin often takes center stage in discussions about blood sugar, another powerful hormone—cortisol—plays a crucial yet often overlooked role in glycemic control. Today, I want to explore how this stress hormone significantly impacts your blood sugar levels and what that means for both diabetic and non-diabetic individuals alike.

The Cortisol-Blood Sugar Connection: A Survival Mechanism

Cortisol is our primary stress hormone, released by the adrenal glands in response to perceived threats—whether that's a charging predator or a looming work deadline. This hormone evolved as part of our "fight-or-flight" response, preparing the body for immediate action by mobilizing energy resources.

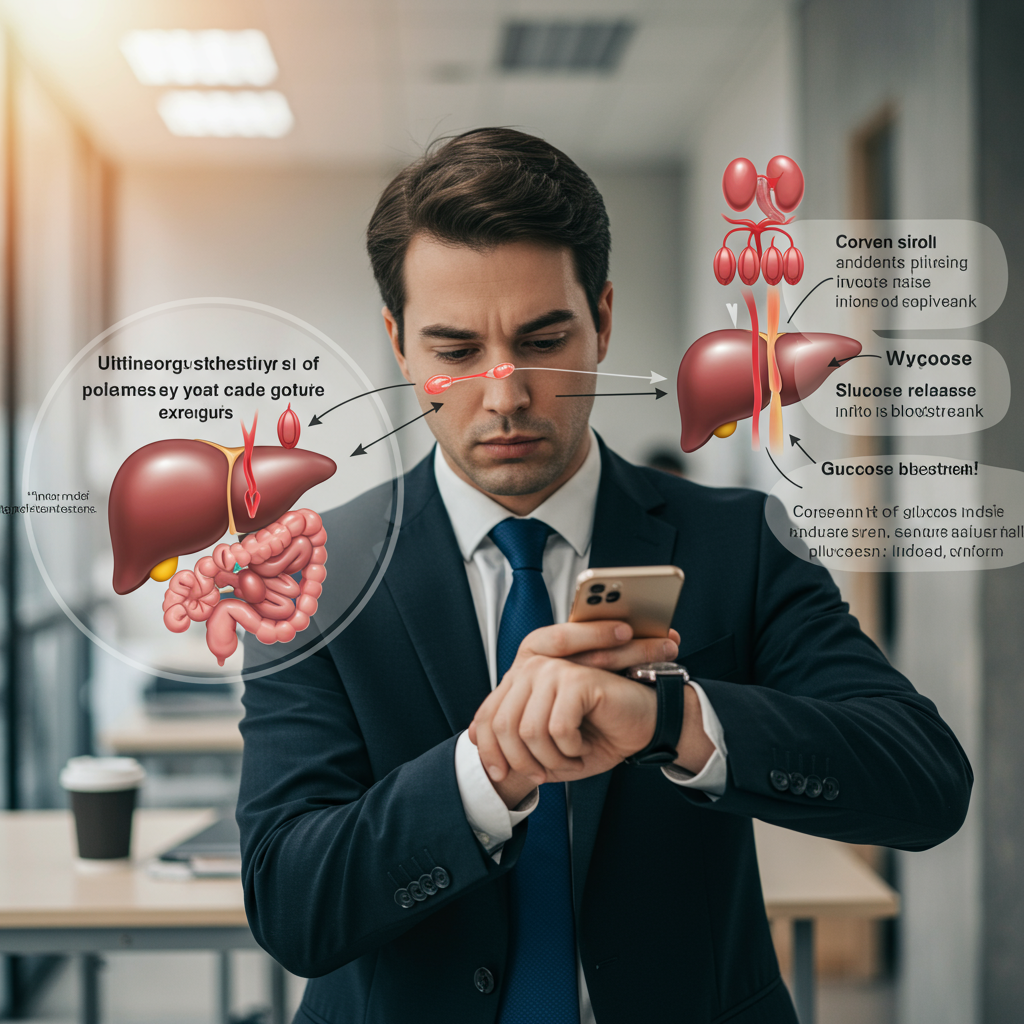

When cortisol is released, it triggers a cascade of metabolic changes designed to increase available energy:

- Gluconeogenesis: Cortisol stimulates the liver to create new glucose from non-carbohydrate sources like amino acids.

- Glycogenolysis: It prompts the breakdown of glycogen (stored glucose) in the liver, releasing glucose into the bloodstream.

- Insulin Resistance: Cortisol temporarily reduces insulin sensitivity in muscle and fat tissues, ensuring more glucose remains in circulation for emergency energy needs.

These mechanisms were evolutionary advantages, providing quick energy when our ancestors needed to flee or fight. However, in our modern world of chronic stress, this same system can contribute to persistently elevated blood sugar levels.

When Stress Becomes Chronic: The Metabolic Consequences

Unlike the acute stressors our bodies evolved to handle, today's stressors are often psychological and persistent. When cortisol remains chronically elevated, several problematic patterns emerge:

Persistent Insulin Resistance: Ongoing stress can lead to sustained insulin resistance, forcing the pancreas to produce more insulin to maintain normal blood sugar. This overwork can eventually lead to pancreatic beta-cell exhaustion—a key factor in type 2 diabetes progression.

Visceral Fat Accumulation: Chronic cortisol exposure promotes fat storage, particularly around the abdomen. This visceral fat isn't just cosmetically concerning—it's metabolically active tissue that further promotes insulin resistance through inflammatory cytokines.

Disrupted Sleep: Cortisol dysregulation often impacts sleep quality, creating a vicious cycle as poor sleep itself raises cortisol levels and reduces insulin sensitivity. A single night of sleep deprivation can temporarily reduce insulin sensitivity by 25% in otherwise healthy individuals.

The consequences are particularly significant for those already managing diabetes. For these individuals, stress-induced blood sugar elevations can become a frustrating obstacle to glycemic control, with "stress hyperglycemia" sometimes resistant to usual insulin doses.

Breaking the Cycle: Practical Approaches to Hormonal Balance

The good news is that understanding this connection gives us leverage points for intervention. Here are evidence-based approaches to mitigate the cortisol-blood sugar relationship:

Deliberate Stress Reduction: Practices like meditation, deep breathing, and mindfulness aren't just wellness trends—they're powerful physiological interventions. Regular meditation has been shown to reduce cortisol levels by up to 20% and improve insulin sensitivity. Even brief (5-10 minute) daily breathing practices can activate the parasympathetic nervous system and reduce cortisol secretion.

Exercise Timing and Type: Physical activity improves insulin sensitivity, but the timing matters. Morning exercise can help regulate the natural cortisol rhythm, while excessive high-intensity exercise late in the day may disrupt sleep hormones. Aim for a combination of resistance training and zone 2 cardio (where you can still maintain conversation) for optimal metabolic benefits.

Sleep Optimization: Prioritizing sleep quality creates a foundation for hormonal balance. Maintain consistent sleep-wake times, limit blue light exposure 2-3 hours before bed, keep your bedroom cool (65-68°F), and consider non-pharmaceutical sleep aids like magnesium glycinate if needed.

Nutritional Considerations: Blood sugar stability itself helps regulate cortisol. Avoid long periods without food, incorporate protein and healthy fats with each meal to slow glucose absorption, and consider limiting caffeine after midday, as it can amplify cortisol response to stressors.

The Broader Perspective: Hormonal Interconnections

What's fascinating about metabolism is how interconnected our hormonal systems are. Cortisol doesn't operate in isolation—it interacts with growth hormone, thyroid hormones, and sex hormones, all of which influence glucose metabolism.

This explains why blood sugar management requires a whole-body approach. When we address sleep, stress, exercise, and nutrition together, we're not just targeting individual pathways—we're optimizing an entire interconnected system.

For those managing diabetes, this perspective offers both challenges and opportunities. While stress may complicate glucose control, stress management becomes a powerful adjunctive therapy alongside traditional approaches. By monitoring not just blood glucose but also recognizing how stress affects your numbers, you gain valuable self-knowledge that can guide more effective management strategies.

The relationship between cortisol and blood glucose reminds us that metabolism isn't simply about what we eat—it's about how our bodies respond to our entire life experience. By respecting this connection, we gain powerful tools for metabolic health that extend far beyond diet alone.

References:

Adam, T. C., & Epel, E. S. (2007). Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology & Behavior, 91(4), 449-458.

Hackett, R. A., & Steptoe, A. (2017). Type 2 diabetes mellitus and psychological stress—a modifiable risk factor. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 13(9), 547-560.